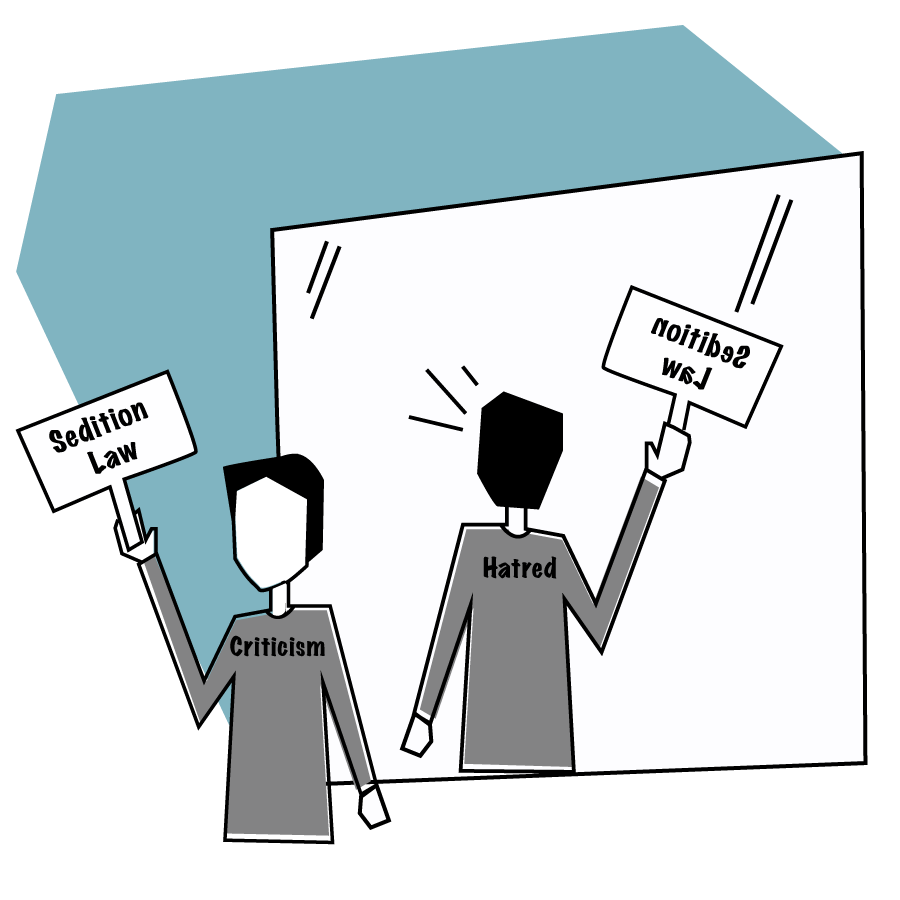

Sedition: Fair Criticism or Inciting Hatred?

The latest

On 11th May 2022, the Supreme Court passed an interim order putting in abeyance the 162-year colonial sedition law u/s 124A of the Indian Penal Code 1860 (IPC). An insight into the section 124A of the IPC which has remained controversial since inception.

Section 124A of the IPC 1860

According to the section, “Whoever, by words, either spoken or written, or by signs, or by visible representation, or otherwise, brings or attempts to bring into hatred or contempt, or excites or attempts to excite disaffection towards, the Government established by law shall be punished with imprisonment for life, to which fine may be added.

The section further explains –

- The phrase “disaffection” includes disloyalty and all feelings of enmity.

- Comments expressing disapprobation of the measures of the Government with a view to obtain their alteration by lawful means, without exciting or attempting to excite hatred, contempt or disaffection, do not constitute an offence under this section.

- Comments expressing disapprobation of the administrative or other action of the Government without exciting or attempting to excite hatred, contempt or disaffection, do not constitute an offence under this section.

Meaning

Simply put, anyone who attempts to incite, instigate or excite disloyalty, enmity or hatred towards the government through spoken or written words, actions or signs, or any visible representation shall be punished with imprisonment or fine. This is a non bailable offence. Such people are barred from government jobs and their passports are seized by the government.

Genesis

The sedition law was drafted way back in 1860 by Thomas Macaulay a British politician- historian, the author of the Indian Penal Code. This was done with the intention of suppressing the voice of dissenters and rebels against British rule in India. However, the sedition law was formally included in the IPC only in 1890.

One of the earliest known cases of sedition was filed against Bal Gangadhar Tilak (1897) for his writings against the monarchy. In fact, three sedition cases were filed against Tilak of which he got convicted in two cases and imprisoned for 6 years. A sedition case was filed against Mahatma Gandhi (1922) for leading a protest march against the British rule. He was convicted and imprisoned as well.

From these cases as well as several others on similar grounds, it can be interpreted that the sedition law was introduced by the British rule only to suppress the natives of their voice, liberty and right(s).

(Mis)use of Sedition law

The biggest challenge is in applying provisions of section 124A IPC to anyone who is perceived as raising their voice against the government or established rule in the country. This is blatant misuse of sedition provisions.

There have been increasing instances of governments, regulatory and enforcement agencies like police invoking this provision to settle scores by implicating people or silence voice of dissent or rebellion.

Sedition law: continuation vs abolition

The sedition law has been the most discussed and debated section in the Indian Penal Code. There are varied views on continuance / abolition of the law.

Why sedition laws can continue

- This provision is required to combat anti-national, secessionist elements and those who pose a threat to the security and sovereignty of the country.

- This provision will ensure stability of an elected government and free them from the threat of a coup or overturning their government through rebellion.

Why sedition laws should be abolished

- The provision was enacted in the colonial British era and has since remained the same. The law has not changed with changing times and that makes it redundant in the present.

- The fear or threat of government rebuke or action to any criticism (made against the government rule) will deter / suppress the voice of the common man. This violates the fundamental right to freedom and speech and expression under Article 19(1)(a) of the Indian Constitution. Fair criticism should be encouraged and not curtailed as it acts as a reality check to democratically elected governments. Freedom of speech and expression and the right to question / criticise is the essence of democracy.

- Some phrases in the provision such as “disaffection” are general in nature and open to varied and ambiguous interpretation.

- Though there have been increased number of arrests or detention under this section, the conviction rate has been dismal. This only strengthens the case of misuse of sedition law.

For instance, thousands of people were charged with sedition for opposing the Citizenship Amendment Act 2019. Similarly, hundreds of farmers were charged with sedition for opposing the farm laws. A young environmental activist was charged with sedition for drafting documents and inciting hatred and disaffection against the government during the farmer’s protest. More recently, a young politician couple was arrested for sedition in a State when they sought to recite a religious hymn outside Chief minister’s residence. They were charged with inciting religious intolerance. In all these cases, sedition could not be proved and hence there was no conviction. - There are other laws like the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act 1967 (UAPA), National Security Act 1978 etc which are more recent and relevant legislations. Hence the colonial era sedition law can be completely done away with.

Court’s perception of sedition

Courts have aligned with changing times and have taken a very objective view on sedition.

In one of the earliest landmark cases i.e, Ram Nandan vs State of Uttar Pradesh [1958 SCC Online All 117], the appellant was arrested for making a speech to a group of villagers criticising the then government for failing to curb poverty and inflation. He was convicted and imprisoned for a period 3 years. On appeal, the Allahabad HC held that section 124A of the IPC was ultra vires Article 19 (1)(a) of the Indian Constitution which guaranteed the fundamental right to freedom of speech and expression. Any restriction should be reasonable. “Legislation which arbitrarily or excessively invades the right cannot be said to contain the quality of reasonableness and unless it strikes proper balance between the freedom guaranteed in Article 19(1)(g) and the social control permitted by Clause (6) of Article 19.

In Kedarnath Singh vs State of Bihar [1962 AIR 955], on similar facts as contained in the above case, the Supreme Court ruled that a crime of sedition can be established under section 124A only if the remarks or words, said or written have the potential to disrupt or disturb public order through use of violence. There should be reasonable restriction imposed on freedom of speech and expression. Criticising government does not mean spreading hatred or violence as long as it is fair criticism.

Over the years, there have been several other cases which have echoed the same thought – use the sedition law with caution.

In 2021, in Kishorechandra Wangkhemcha v. Union of India [WP (C) 682/2021] two journalists were charged with sedition after they posted comments and cartoons criticising the Chief minister of a State. They filed a petition before the Supreme Court stating that the judgment in the Kedarnath Singh case imposing reasonable restrictions will no longer hold good due to the changed socio-economic scenario. Additionally other legislations involving safety, national security and public order are also in place. This makes the sedition law obsolete. The ambiguous interpretation of section 124A only encourages misuse of the provision.

The road ahead

The above petition filed by a group of journalists, a retired army general and media house(s) is pending a final judgment by the Hon’ble Apex Court. It is in this case that the Hon’ble Supreme Court held directed the central government to re-examine and reconsider the continuation or abolition of the colonial era sedition law.

Till the government submits its report, the Supreme Court has put on hold the sedition law. This means that no new cases of sedition can be filed under section 124A till the Central government re-examines and re-considers the provision. No trial shall commence or continue in the existing cases. Effectively, all cases are suspended. The intention of the Hon’ble Supreme Court is evident in the interim order. The final judgment on the matter is awaited.