Japanese Law on Surname: A Debate between Culture and Freedom

In this world, women represent almost half of the population and contribute equally to growth and development, however, they are still being subjugated and are treated unfairly. Primarily, the essential reasons for such unequal treatment are the human-made laws and customary practices which are influenced by the ideas of male supremacy and patriarchy resulting in keeping women on a different and lower pedestal. One such example of an unfair law that promotes male supremacy and restricts the autonomy of women is the law on surname in Japan which mandates the married couple to share the same surname.

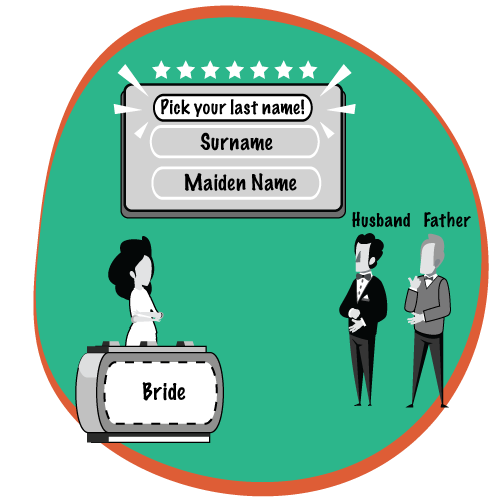

Article 750 of Japan’s Civil Code enunciates that “Husband and wife assume the surname of the husband or wife in accordance with the agreement made at the time of the marriage.” Although the law has not directed any spouse to adopt the surname of any particular counterpart, however, in 96 percent of the cases,1 women drop their maiden name and adopt the surname of their husband as an obligation to the customary practices which came to be first introduced in 1896 during the Meiji era (1868-1912) in which the women left its house and became the part of the husband’s family.

The debate to bring legal reforms in this particular field has remained a controversial topic for almost two decades but nothing substantial has ever been done, rather, an approach protecting the law has been time and again celebrated. Nonetheless, in a recent move, a new ray of hope has been observed after Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga of Japan reiterated during a parliamentary session that he has long voiced support for a system where members of the same family could have different surnames.2

Seemingly, the opinion of the Prime Minister has resulted in fierce opposition and has again resulted in a never-ending debate between the liberals and conservative ideologies, where the motion to change the law is been debated tactfully.

The centre of the debate revolves around the issue of protecting traditional practices at one end and freedom of choice on the other end. The supporters of the law believe that if freedom is given to make certain choices, there is a potential risk of family ties getting weakened resulting in unwarranted troubles in a marital relationship. Moreover, in support of their argument, the Supreme Court of Japan in December, 2015, has held that Article 750 of the Civil Code requiring common surname is not unconstitutional as it is an “established institution and has rational”. Although 5 out of 15 judges found it to be unconstitutional, majority uphold the law, thereby making the mandate of law enforceable to date. Mostly, the people with conservative ideologies are in support of keeping this law intact as they believe it to be sacrosanct.

Contrarily, there is a section of society that finds this law to be archaic and patriarchal believing that such law creates an unnecessary impediment to the rights of women. It is because firstly sudden change of name causes inconvenience to women as they have to get their names amended in all the public documents and undeniably, such process itself is tedious and requires a lot of time. Secondly, such a law creates a restriction on the right to autonomy and freedom of choice as women are bounded to submit their surnames in front of their husband’s surname as per the customary practices. Those who are in favour of reversing and removing this law belong to a liberal set of views and believe in categorical morality. To abolish this law and the arbitrariness resulting out of it, United Nations Committee on Elimination of Discrimination against women is also supporting the movement with a higher aim of eliminating the tenets of patriarchy in Japan.

Law on Surname in different countries

Not only in Japan, but the practice of adopting the surname of their husband is found even in India as well. Although, there is no specific law governing the same but Indian society mostly worships the traditional practices and within that adopting the surname of the husband of is one. The Statistics are also not good in Britain where it has been found that 90% of the women take the surname of their husband after marriage.3

The comparable position was also found in Switzerland before 2013 where law compelled the wife to take their husbands surname or have the double surname, however in 2013, the law has been reformed and now the women are allowed to keep their surname or the spouses can choose either the woman or the man’s surname as their married name.

Contrary to such practice, French law ensures that there is no obligation on women to change their maiden name after marriage and therefore, a married woman is allowed to keep her family name or can even keep a double-name. Similarly, the law of surname in Greece is very strict as they believe surname to be a trait of personality. In Greece, if one has to change the surname, an application has to be submitted to the Prefect by the interested party in which it has to be mentioned in detail the reason for which this specific change is sought, whereas it has to be stated the surname which is favorable to be acquired.4 Coming to Iceland which is also known as the country of no surnames, because there are no family names and further one cannot take the name of the spouse after marriage. Men and Women in Iceland keep their father’s surname as their maiden name.

Where does the solution lie

It is irrefutable that the notion of patriarchy is well-rooted within the functionality of the society. Moreover, with the new waves of development coming into the process, the concept of male-domination is constantly snowballing. The flow of patriarchy in different traditional practices has now even rooted into modern technologies such as Artificial Intelligence, etc. Therefore, at one side if the society is claiming the evolution of equality, it is necessary to calculate the other side which is at the same time pushing forward the ideal situation of patriarchy.

To reduce the tension in this non-harmonious situation, the solution lies in the fundamentals of the respective nations. The governments of each state must ensure that concept of equal treatment is not just pronounced in parliaments but also implemented within the state. The laws that are being made at present or even the archaic laws which are already in force, it is essential that such laws should pass the test of constitutional validity where these laws are examined on the touchstone of equality and non-arbitrariness towards any gender. Only those laws should be allowed to regulate the sovereign which have passed the mentioned test. In a democratic regime run on the pillars of equality; freedom and autonomy cannot be a blessing to a percentage of society, rather, it should flow like a stream without any concrete dam blocking the path.

References