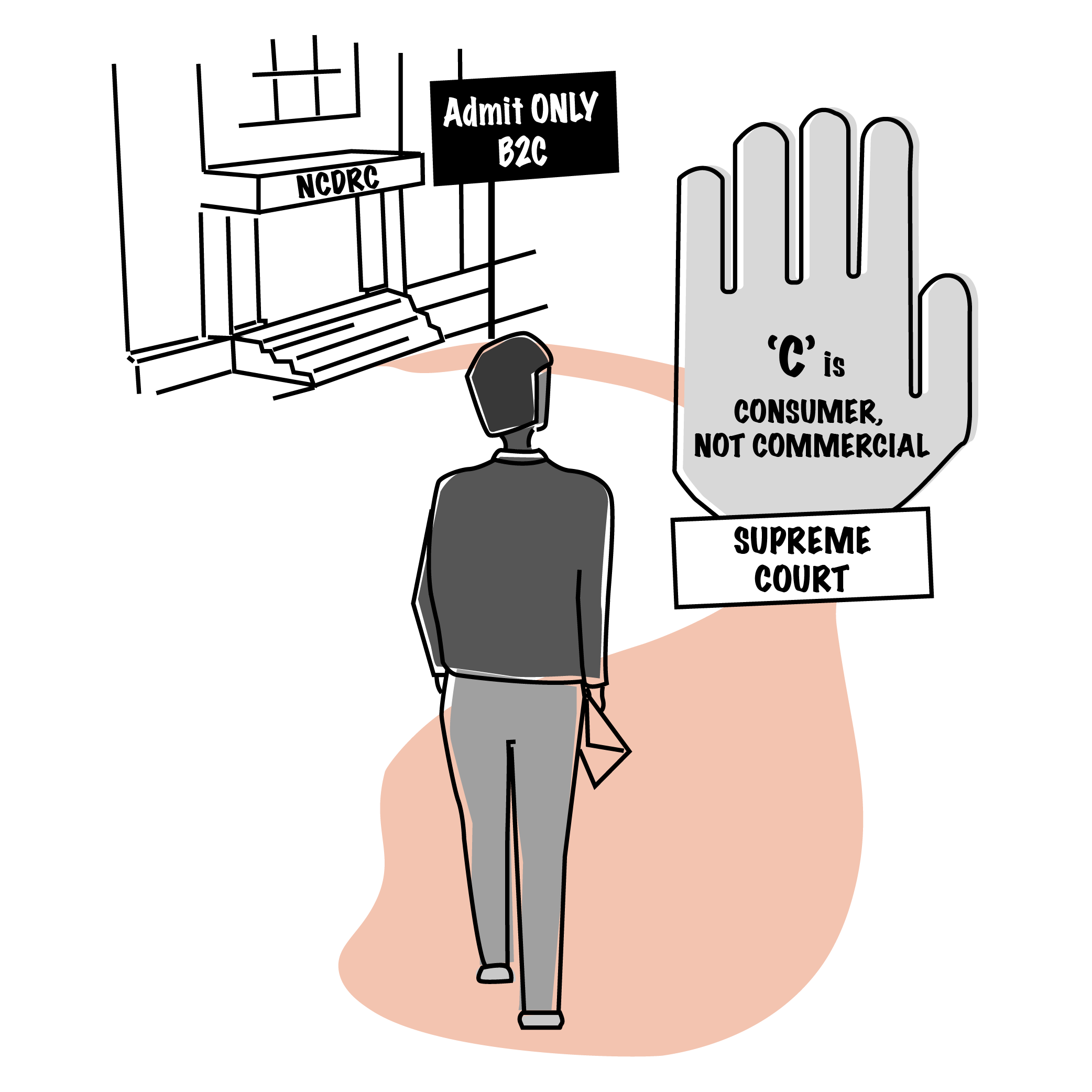

Person availing banking services for commercial purpose – Not Consumer

In the Supreme Court of India, Civil Appellate Jurisdiction

Civil Appeal No.11397 of 2016

SHRIKANT G. MANTRI …………… Appellant(s)

Vs

PUNJAB NATIONAL BANK ….…. Respondent(s)

On 22nd February 2022, a division bench comprising Justice L Nageswara Rao and Justice B R Gavai ruled that a person availing the services of a bank for ‘commercial purpose’ is not a consumer under the Consumer Protection Act. While passing this judgment, the bench also stated that there cannot be a strait jacket formula to arrive at this conclusion and each case shall be decided based on the facts and evidence placed on records.

A look at the case highlights in brief:

Facts:

- The appellant (hereinafter referred to as “Shrikant”) a stock broker by profession opened an account in 1998 with Nedungadi Bank, now called Punjab National Bank (hereinafter referred to as the “Bank”). He also worked as stock broker for the Bank.

- Shrikant regularly applied to the Bank for overdraft (“OD”) facilities in connection with his day to day share and stock transactions. In 1998, the Bank sanctioned an OD facility of Rs. 1 Crore for which Shrikant pledged his shares worth more than Rs. 1 Crore as security with the Bank. Subsequently, in 1999 Shrikant applied for enhancement of OD facility from Rs. 1 Crore to Rs. 5 crores. The Bank sanctioned the same.

- In 2001, Shrikant sought a temporary OD facility from Rs. 5 Crores to Rs. 6 Crores for a period of one week. The Bank called upon Shrikant to pledge additional shares due to the steep fall in the share market. Shrikant pledged an additional 37,50,000 equity shares of Rs. 10/- each of an unlisted company, Ansal Hotels Ltd. Subsequently Ansal hotels Ltd merged with ITC Hotels Ltd. Due to which the shares of 37, 50,000 equity shares of Ansal Hotels Ltd became 3, 75,000 shares of ITC Hotels Ltd.

- In 2001, the OD account of Shrikant became irregular due to which the Bank called upon Shrikant to regularize the same and asked him to pay up Rs. 600.61 lakhs (Rs. 6 Crores) with interest thereon. Shrikant instructed the Bank to sell shares pledged by him as security to close the overdraft account. However, the Bank did not sell the shares in 2001. In 2002, the shares were sold by the Bank when the market value was it’s lowest which resulted in huge loss to Shrikant.

- From the sale of a part of such shares, the Bank could recover approximately Rs. 2.69 Crores only. As a result the Bank filed a recovery petition before the Debts Recovery Tribunal, Mumbai against Shrikant. Though the Tribunal passed a decree, the parties reached a one-time settlement for payment of Rs. 2 Crores.

After such settlement, the Bank withdrew the petition before the DRT and also issued a “No dues” certificate against the overdraft facility in May 2005. - However, in June 2005, Shrikant filed a complaint before the Commission alleging deficiency in services on the part of the Bank. He sought relief by seeking return of the 3, 75, 000 shares of ITC Ltd along with dividend and all accretions thereon.

- With reference to Bank’s transactions with Shrikant in his capacity as a stock broker, the Bank initiated an arbitration proceedings in Mumbai. Shrikant stated that the arbitration in favour of the Bank failed.

- The main contention of the Bank before the Commission was that Shrikant was not a consumer u/s 2(1) (d) of the Consumer Protection Act. The forum held that Shrikant had availed services of the Bank for “commercial purpose” and therefore was not a consumer under section 2(1) (d) of the Act.

- Aggrieved by the order of the Commission, Shrikant approached the Hon’ble Supreme Court by way of an appeal.

Issue

- Whether services availed by Shrikant from the Bank would fall within the term ‘commercial purpose’

- Whether services are exclusively availed by Shrikant for the purposes of earning his livelihood by means of self-employment.

Contention(s)

Shrikant (Appellant)

Counsel for Shrikant contended that:

- Shrikant had a dual relationship with the Bank – one as a ‘consumer’ and another as a ‘stock broker’. The OD facility taken in his capacity as a consumer for the purpose of his self-employment. Shares were pledged against the OD facility taken.

- There were no dues outstanding in the OD account due to the one time settlement taken / compromise reached between Shrikant and the Bank. The “No dues” letter given by the Bank to Shrikant was proof of the same. Despite that the Bank continued to hold his pledged shares illegally. They were not returned despite repeated requests.

- The arbitration proceedings were between the Bank and Shrikant in his capacity of working as ‘stock broker’ for the Bank. The arbitration proceeding reached its finality.

- Though section 2(1)(ii) of the Consumer Protection Act excludes a person availing services for ‘any commercial purpose’, the explanation would serve as a proviso to proviso to include even such a person if it is shown that such services were availed by him exclusively for the purpose of earning his livelihood by means of self-employment. Since Shrikant was engaged in the profession of stock broker and required to take OD facility for his profession, it can be considered that the Bank was rendering services for his livelihood which is covered under the proviso to definition of a ‘consumer’. Relying the judgment in Internet and Mobile Association of India vs. Reserve Bank of India, (2020) 10 SCC 274 it was contended that the services of a Bank provide lifeline to any trade, profession or business in the present era. Hence Shrikant would come under the definition of a ‘Consumer’ under the Consumer Protection Act. Other case laws were relied upon as well to strengthen this argument such as Lilavati Kirtilal Mehta Medical Trust vs. Unique Shanti Developers and others, (2020) 2 SCC 265 and Sunil Kohli and another vs. Purearth Infrastructure Limited, (2020) 12 SCC 235.

Punjab National Bank (Respondent)

Senior counsel appearing for the Bank contended that:

- The Consumer Protection Act is a special statute enacted for providing speedy and simple redressal of consumer disputes. The Act contains procedures in such a way that disputes are settled without any delay. Laxmi Engineering Works vs. P.S.G. Industrial Institute, (1995) 3 SCC 583.

- If the definition of ‘Consumer’ is expanded to include person(s) who avail services for commercial purposes, the very purpose of the Act would be defeated ad it would open floodgate of complaints.

- Apart from being inconsistent from the provisions of section 2(1)(d)(ii) of the Act, it will deny provision of speedy justice to aggrieved consumers.

Judgment

In arriving at a conclusion, the Bench considered the following:

- Section 2(1)(d) of the Consumer Protection Act is divided into two parts:

- Section 2(1)(d)(i) deal with buying goods

- Section 2(1)(d)(ii) deals with hiring of services

Ever since its enactment, the definition of ‘Consumer’ has undergone amendments from time to time in keeping with the main objective of speedy redressal of consumer grievances.

The amendment to the Consumer Protection Act in 2002 further clarified that that the ‘commercial purpose’ does not include use by a person of goods bought and used by him and services availed by him exclusively for the purposes of earning his livelihood by means of self-employment. This amendment was done with the twin objective of (i) keeping commercial transactions beyond the ambit of the ‘Consumer’ and (ii) if services were availed by him exclusively for the earning his livelihood by self-employment, he would still be a consumer. The intent of this was to bring the clarity of definition of ‘services’ on par with that of ‘goods.’

For instance a person who purchases an auto rickshaw to ply it himself for earning his livelihood (by self-employment) shall be considered as a ‘Consumer’. However, if a person purchases an auto rickshaw to be operated exclusively by another person, would not be considered a ‘Consumer’.

The Bench was of the view that there cannot be a strait jacket formula in determining whether a transaction is for ‘commercial purpose’ or not. It shall depend on facts and circumstance on each case.

Whether a transaction is for commercial purpose would depend upon:

- Nature of purpose – Normally commercial purpose is understood to include manufacturing / industrial activity or business to business transactions between commercial entities;

- Nexus to profit – Purchase of goods or services should have a direct and close nexus with profit generating activity;

- Dominant intention / purpose – whether the transaction facilitates some kind of profit generation for the purchaser or their beneficiary.

- Dominant use – whether the purpose behind purchasing the good or service was for personal of purchaser or their beneficiary or is otherwise linked to any commercial activity.

In the present case, the Commission concluded that Shrikant opened an account with the Bank, took overdraft facility to expand his business profits, and subsequently from time to time the overdraft facility was enhanced so as to further expand his business and increase his profits. The relationship between Shrikant and the Bank is purely “business to business” relationship. As such, the transactions would clearly come within the ambit of ‘commercial purpose’. It cannot be said that the services were availed “exclusively for the purposes of earning his livelihood by self-employment”. If it had to be interpreted that way, then business disputes would also become consumer disputes which would defeat the very purpose of the Consumer protection Act of speedy redressal of consumer disputes.

The Bench agreed with the judgment of the Commission and ruled that for the purpose of this case, Shrikant would not be considered as ‘Consumer’ under the Consumer act. Therefore services availed by him with the Bank would be considered for ‘commercial purpose’ and not for purpose of earning livelihood by means of self-employment. The Bench accordingly dismissed the appeal filed by Shrikant.

Full text of the Judgment:

https://main.sci.gov.in/supremecourt/2016/30722/30722_2016_5_1501_33588_Judgement_22-Feb-2022.pdf