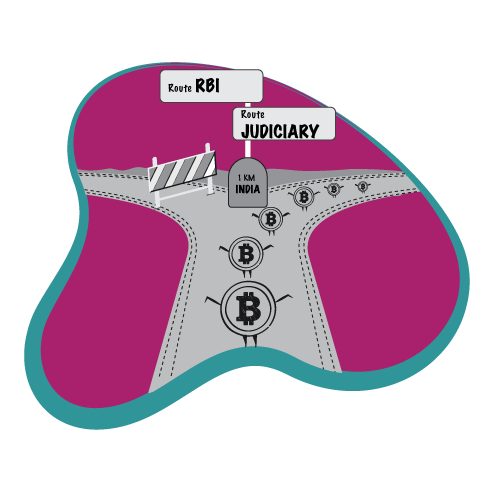

SC Lifts Ban on Cryptocurrency Imposed by RBI

In the Supreme Court of India Civil Original Jurisdiction

Writ Petition (Civil) No.528 of 2018 With Writ Petition (Civil) No.373 of 2018

INTERNET AND MOBILE ASSOCIATION OF INDIA …… Petitioner

vs

RESERVE BANK OF INDIA …….. Respondent

On 4th March 2020, a three Judge bench comprising Justice Rohinton F Nariman, Justice Aniruddha Bose and Justice V. Ramasubramanian, set aside an RBI notification issued in April 2018 that prohibited use of banking channels for transactions using cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin. Understandably, this judgment has evoked mixed response. While technology heads have welcomed the decision, regulators are mulling over further legal action over security concerns of transacting in cryptocurrency. A look at the basics of cryptocurrency before analysing the Judgment:

CRYPTOCURRENCY: DECODED

Simply put, cryptocurrency is virtual currency. It is a type of unregulated digital money, issued and controlled by its developers and used and accepted by the members of a specific virtual community. Such currencies are not in the physical form of notes or coins. They are virtual and not routed through any normal banking channels. It is a digital asset using cryptography to secure financial transactions, create additional units of virtual currency and transfer the assets. Cryptocurrency works on a decentralized control mode through a block chain technology that serves as a public financial database. Bitcoin that was released in 2009 is considered as the first cryptocurrency.

FACTS

On 5th April 2018, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) issued a statement called the Statement on Developmental and Regulatory Policies. Paragraph 13 of the said statement prohibited entities regulated by RBI not to deal with or provide services to entities dealing with virtual currencies.

Following the Statement, RBI also issued a circular dated April 6, 2018, in exercise of the powers conferred by Section 35A read with Section 36(1)(a) and Section 56 of the Banking Regulation Act, 1949 and Section 45JA and 45L of the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934 (hereinafter, “RBI Act, 1934”) and Section 10(2) read with Section 18 of the Payment and Settlement Systems Act, 2007. The circular reiterated the Statement issued the previous day directing entities regulated by RBI (i) not to deal in virtual currencies nor to provide services for facilitating any person or entity in dealing with or settling virtual currencies and (ii) to exit the relationship with such persons or entities, if they were already providing such services to them.

Challenging the Statement and the Circular, The Internet and Mobile Association of India (IMAI), an independent and specialized body which represents the interests of online and digital services industry filed a writ petition. Following this, few other companies, stakeholders of cryptocurrency and individual crypto dealers filed another writ petition.

ARGUMENT(S)

The Regulators’ apprehension

The RBI has been consistently viewing it from the perspective of a regulator. World over the issue has been in limelight since 2013. Several papers and working committee reports have been presented to the government, regulators and the public to spread awareness of the cryptocurrency. In December 2013, the RBI issued a press release cautioning the users, holders and traders of virtual currencies about the potential financial, operational, legal and customer protection and security related risks that they are exposing themselves to. The Press Release noted that the creation, trading or usage of VCs, as a medium of payment is not authorized by any central bank or monetary authority and hence may pose several risks.

The RBI contends that while technological innovations and virtual currencies have the potential to improve efficiency and inclusiveness of financial systems, they also pose a challenge to consumer interest, market integrity and money laundering and terror financing. The RBI has been regularly stating that while the advantages of dealing with virtual currency were (i) control and security, (ii) transparency and (iii) very low transaction cost, the disadvantages indicated were risk and volatility.

It is the contention of the regulator that cryptocurrency eco-system may affect the existing payment and settlement system which could, in turn, influence the transmission of monetary policy. Such currencies do not have any grievance / consumer dispute redressal system.

Furthermore, being stored in digital/electronic media – electronic wallets – it is prone to hacking and operational risks. There is no established framework for recourse to customer problems/disputes resolution as payments by cryptocurrencies take place on a peer-to-peer basis without an authorised central agency which regulates such payments.

Besides, it is open to being used for illicit activities such a money laundering, terror financing and tax avoidance. The absence of information on counter parties in such peer-to-peer anonymous systems could subject users to unintentional breaches of anti-money laundering laws (AML) as well as laws for combating the financing of terrorism (CFT).

While Japan and South Korea account for the highest cryptocurrency trading in the world, China altogether banned the same citing the similar reasons as contended by the RBI back home. Hence the inter-ministerial committee, in February 2019 recommended a ban on the cryptocurrency.

Intention of Cryptocurrency backers

The petitioner(s) have been maintaining that the RBI has no power to prohibit the activity of trading in virtual currencies through VC exchanges since are tradable commodities/digital goods which are outside the purview of the regulatory framework of the RBI Act, 1934 or the Banking Regulation Act, 1949. They do not even fall under the credit system of the country to be governed by the RBI Act. Sections 45JA & 45L do not provide scope of covering the virtual currency under the purview of the RBI Act.

The power to issue directions “in the public interest” u/s Section 35A(1)(a) of the Banking Regulation Act, 1949 and the power to caution or prohibit banking companies against entering into any particular transaction conferred under Section 36(1)(a) do not extend to the issue of blanket directions that would deny access to the banking services of the country by virtual currency exchanges.

The power conferred on RBI to issue guidelines u/s 10(2) of the Payment and Settlement Systems Act, 2007 and to give directions pertaining to the conduct of business relating to payments systems, exercisable in public interest upon being satisfied, is also not applicable to virtual currency exchanges, as the services rendered by them do not fall within the definition of the expression “payment system” under Section 2(1)(i) of the said Act.

The petitioners further contended that the RBI did not apply its mind to the issue as all other key economic and finance departments of the government have recognized the beneficial aspects of cryptocurrency. They have only recommended a regulatory regime to be put in place. They further reiterated that not all cryptocurrencies are anonymous. The RBI has clearly not looked at this aspect and instead advocated a blanket ban.

THE JUDGMENT

In a detailed 180page Judgment, the Full bench ruled:

- The preamble of the RBI Act itself states that the statutory obligation that RBI has, as a central bank is to (i) operate the currency and credit system, (ii) regulate the financial system and (iii) ensure the payment system of the country to be on track, would compel them naturally to address all issues that are perceived as potential risks to the monetary, currency, payment, credit and financial systems of the country. If an intangible property can act under certain circumstances as money (even without faking a currency) then RBI can take note of it and deal with it. That being the case, the contention of the petitioners that the cryptocurrency activity does not come under RBI purview will not hold good. Therefore, anything that may pose a threat to or have an impact on the financial system of the country, can be regulated or prohibited by RBI, despite the said activity not forming part of the credit system or payment system. The expression “management of the currency” appearing in Section 3(1) need not necessarily be confined to the management of what is recognized in law to be currency but would also include what is capable of faking or playing the role of a currency. It is well established that virtual currencies are a threat to the financial system. The Apex court ruled that it is very much within the ambit of the RBI to deal with, regulate or prohibit anything that may pose a threat to the economy.

- For the RBI to take pre-emptive action, it must prove that there is some co-relation, some damage suffered by entities regulated by it. In this case that has not been established least some semblance of any damage suffered by its regulated entities but there is none.

- The petitioners have taken a stand that virtual currencies (such as cryptocurrency) are not money or other legal tender, but only goods / commodities falling outside the purview of the RBI Act, 1934, Banking Regulation Act, 1949 and the Payment and Settlement Systems Act, 2007. In fact, the impugned Circular of RBI dated 06-04-2018 was issued in exercise of the powers conferred upon RBI by all these three enactments. Therefore, if virtual currencies do not fall within subject matter covered by any or all these three enactments and over which RBI has a statutory control, then the petitioners will be right in contending that the Circular is ultra vires.

For the above reasons, the Apex Court held Circular dated 6th April 2018 was set aside.

Note: For full text of the Judgment

https://main.sci.gov.in/supremecourt/2018/19230/19230_2018_4_1501_21151_Judgement_04-Mar-2020.pdf